The Fed’s Higher Fed Funds Rate Projections Mean What?

Before they were awash with reserves, banks often paid interest to other banks in the “federal funds” market if they needed more reserves to support more lending (due to reserve requirements). Since 2008 and massive “quantitative easing” (buying federal debt with new reserves), reserve requirements stopped limiting commercial bank credit. The Federal Reserve instead paid an interest rate on reserve balances (IROB)– which effectively sets a floor under the fed funds rate.

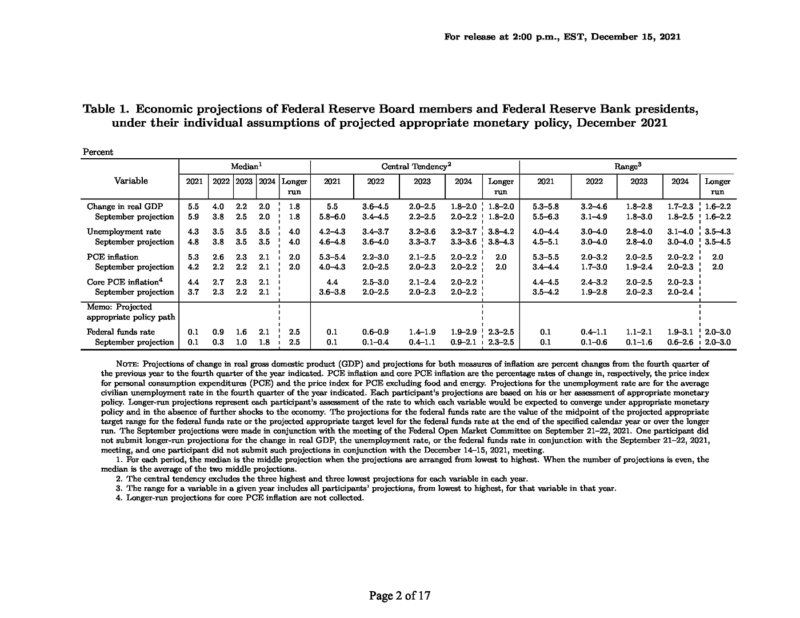

Members of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed’s policymaking arm, announced on December 15 that their median projection for the fed funds rate would rise from 0.1% this year to 0.9% in 2022, 1.6% in 2023, 2.1% in 2024 and 2.5% over some “longer run.” It necessarily follows, under the post‐2008 regime, that the Fed will be obliged to pay comparable interest rates on reserve balances – which is now the only rate presumably intended to restrain the flow of new bank deposits (money) created by new loans.

The announcement that the FOMC predicted (rather than planned) that the fed funds rate would be 4–8 basis points higher than they said in September was universally interpreted as a signal that the Fed would be “tightening” monetary policy. But that depends on some specific but unexplained theory and facts about how monetary policy works. If high inflation causes high interest rates, as Irving Fisher famously taught, it does not make much sense to expect high interest rates to cure inflation (which would lower nominal interest rates if it worked). The notion that a higher interest rate on reserves is per se evidence of “tightening” also depends on some theory and facts about whether the Fed leads or follows worldwide swings in inflation or interest rates.

The fed funds rate averaged 9.8% a year from 1980 to 1990. Was that because the Fed was following a “tight” policy to avoid inflation? Not if we judge policies by results.

The fed funds rate averaged less than 1.4% from 2002 to 2019. Was that because the Fed was following an “easy” policy to raise inflation? If so, it failed.

Japan has long had interest rates of zero or less, but inflation in consumer prices (unlike imported commodities) remains extremely low. Irving Fisher could explain that, but it defies defining high short‐term rates as a weapon against inflation.

The new FOMC projections raised next year’s projected PCE inflation to 2.6%, up from 2.2% in September and from the CBO’s July estimate of 2.1%.

News of the Fed’s somewhat higher projected interest rates to be paid on bank reserves left the 10‐year bond yield around 1.4–1.5%, so that trying to push the IROB higher than that might invert the yield curve enough to provoke a recession (which eventually pulls bank rates back down).

It is rarely prudent to assume that a central bank’s central planners can predict the future better than you can, or that they really know what they are doing and why.

Reprinted from the Cato Institute