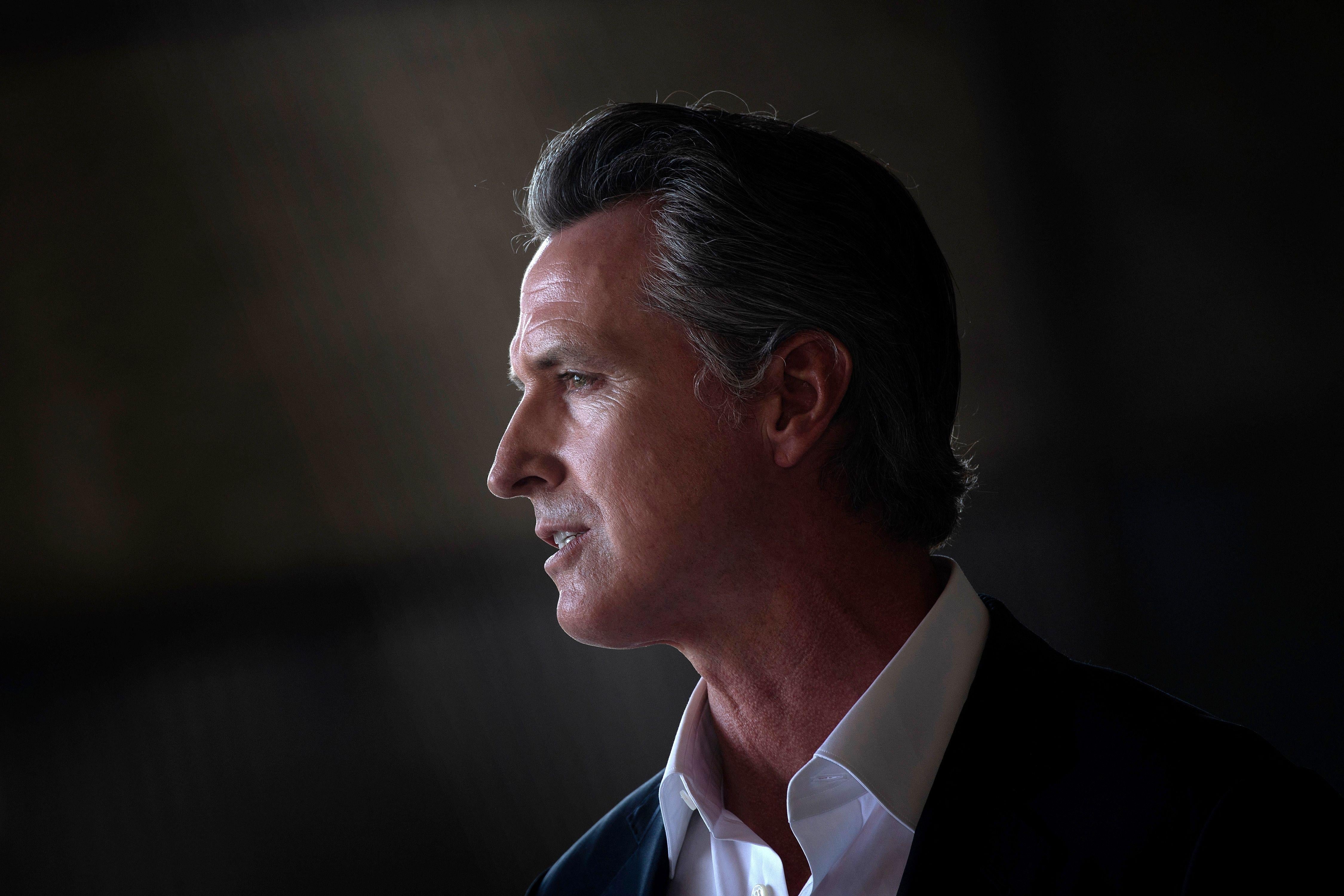

On Thursday, with the stress of the recall election firmly behind him, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that effectively abolishes single-family home zoning in the country’s largest state. Senate Bill 9 allows owners to split their lots or convert homes to duplexes, regardless of local zoning, in an effort to increase the state’s anemic housing production, open up high-opportunity neighborhoods, and lower rents and home prices.

The law raises the possibility that many single-family homes currently protected by zoning could be replaced by two units—or even four, if owners split their lots and build duplexes on each half.

Naturally, opponents of exclusionary zoning—a practice with a racist history that has severely curtailed housing supply in many California cities, taking the state’s median home price north of $800,000—were really excited about SB 9. Local officials, homeowner groups, and the California Republican Party threw a fit, with the anti-growth group Livable California decrying a “luxury housing bill that destroys your neighborhood”—a liberal glaze on the end-of-the- suburbs fearmongering that Donald Trump attempted to employ against Joe Biden last year.

Symbolically, the passage of SB 9 is a huge deal in the national movement to break down the apartment bans that effectively segregate American cities and shows just how far the policy window has shifted in the past five years. A handful of smaller jurisdictions, including the state of Oregon and cities such as Minneapolis and Charlotte, have taken steps in the same direction.

On the ground, however, the reality will not be instant housing abundance—or the destruction of the suburbs, for better or for worse. Zoning is a powerful obstacle to denser, more affordable development—but reforming zoning can only do so much.

That was one of the conclusions of a July study by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California–Berkeley, which reported that SB 9 would be relevant to just 1 in 20 single-family-home parcels in California. That’s partly thanks to a combination of loopholes in the law, including protections for existing renters and exemptions for historic districts and fire hazard zones. Building duplexes at scale is all but prohibited by the bill’s condition that the same owner can’t split adjacent lots.

But the largest limitation by far is simply that lightly densifying most parcels won’t pencil: Buying and building in California is expensive. Once you take development costs into account, SB 9’s territory narrows from 6 million to 410,000 parcels. On millions of parcels, the possible revenues from a duplex just aren’t high enough to justify the investment.

That’s still a lot of potential new units in a state that grants permits to just 100,000 units a year. But what’s feasible doesn’t happen overnight. Homeowners don’t always act to maximize their financial prospects, and those who try may have trouble securing financing.

To understand how the abolition of single-family zoning might play out in California, consider the state’s long, slow shuffle toward permitting accessory dwelling units, such as granny flats, backyard cottages, or garage apartments. The state first required cities to permit ADUs in 1982, but cities and suburbs erected so many regulatory barriers that it was really hard to build a legal ADU, and most existing ADUs were illegal. It took another 34 years for the statehouse to get serious about ADU legalization, and it still took the passage of no fewer than five separate bills, starting in 2016, to dismantle the various local impediments once and for all.

Today, California is cranking out ADUs, with Los Angeles alone issuing more than 5,000 permits a year. Even so, at this rate it will take hundreds of years for the state to reach what the Terner Center reckons are the 1.8 million ADUs that could be economically and legally built today.

With respect to duplexes, municipalities can (and probably will) throw up a number of obstacles to stifle SB 9’s impact, including height limits, floor-area ratio rules, minimum lot sizes, and development fees. Many of those issues may need to be addressed by the California Legislature in a future session, overriding local politicians who fear homeowner revolts and relish the power they wield to issue exemptions to strict zoning laws.

“I see this as an iterative process similar to how ADUs progressed,” said David Garcia, the policy director at the Terner Center and one of the authors of the SB 9 impact analysis. “It wasn’t enough to say they were allowed. Lawmakers had to be proactive about eliminating setback requirements, reducing impact fees, wiping away owner-occupancy requirements—those were all separate bills.”

Zoning is a hurdle, but it’s not everything. The reason SB 9’s potential effect is so modest is not regulatory barriers, but development costs. Buildings costs in California are really high, on account of both labor and materials. Duplexes are a low-margin business, and the law is all but designed to discourage industrial-scale duplex production. In much of the state, costs have gotten so high it may take more substantive upzoning to justify buying and demolishing a single-family home.

Neighborhoods comprised exclusively of single-family homes are technically obsolete now, but in reality, they aren’t going anywhere.