On an intellectual level, I realize that there’s no good reason to panic about this whole monkeypox thing—or even to be particularly worried about it. Truly, I get that.

But my lizard brain? My perpetually anxious, mildly hypochondriacal id that currently plays a daily game of “COVID or allergy season”? Yeah, it’s on high alert, thank you very much. We’re still dealing with one unresolved pandemic, and now Small Pox Lite is on the rise? I mean, how is this not a joke?

Rarely seen outside of West Africa, 144 confirmed and suspected cases of monkeypox have suddenly and mysteriously emerged across Europe, the UK, Israel, and North America in recent weeks, according to a tracker compiled by a group of infectious disease experts. Here in the United States, there is one identified case in Massachusetts—the man had recently traveled to Canada, where a cluster has been found—and a possible infection in New York City. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are also monitoring six people who sat near an infected passenger during a flight from Nigeria.

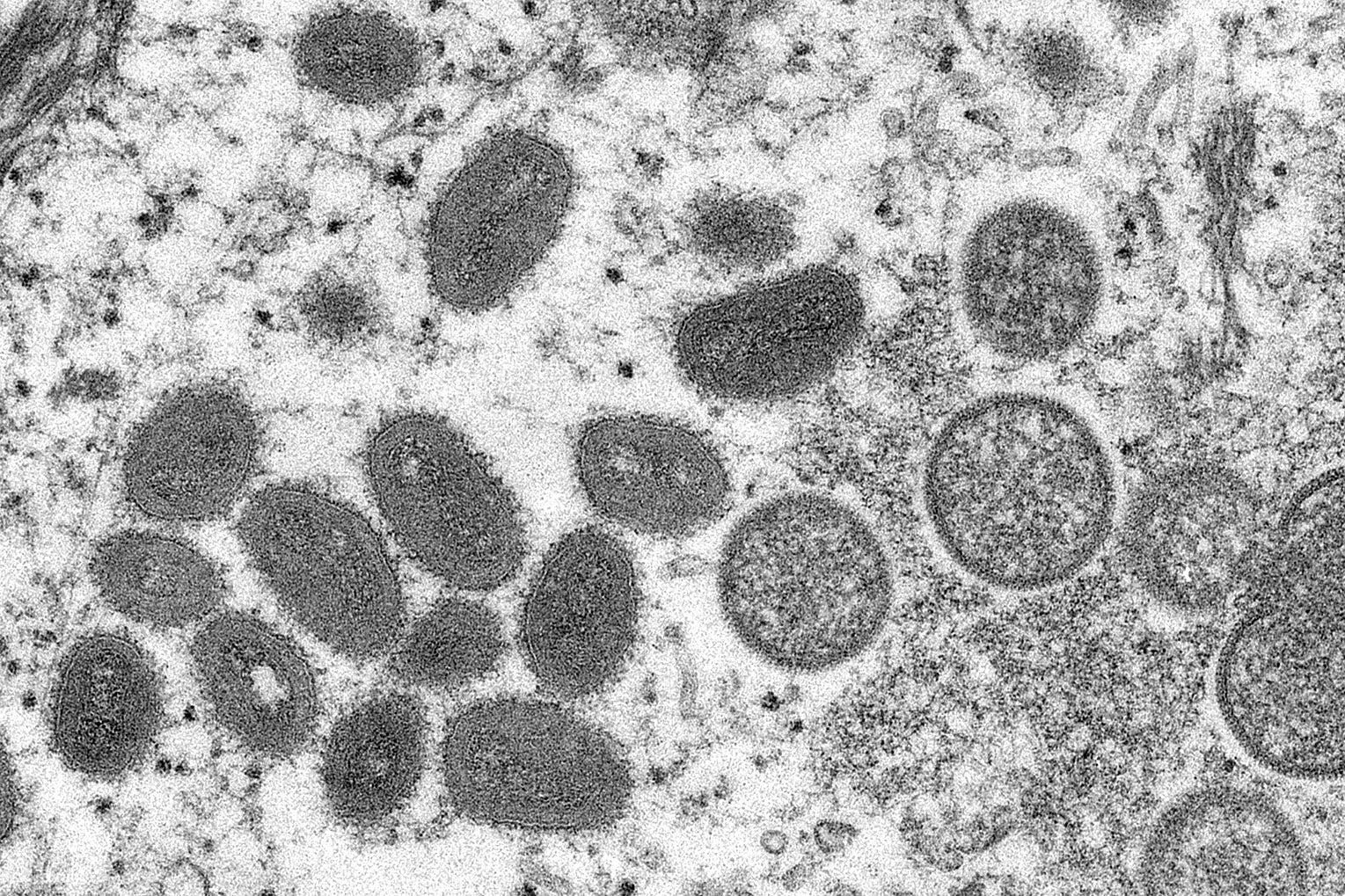

Monkeypox is a milder, less deadly viral cousin of smallpox (both belong to the genus Orthopoxvirus.) It causes flulike symptoms as well as a horrendous rash that can spread across the body and forms large pustules that eventually scab off and scar. It looks biblical, like something Moses brought down on the Egyptians.

That is to say, I would personally prefer not to get this potentially deadly illness. The version of the virus found in West Africa, which is what so far appears to be spreading worldwide, has a fatality rate of about 1 percent, according to the World Health Organization. (A version found in the Congo River basin has a kill rate of about 11 percent). As NBC notes, “There is not a proven treatment for monkeypox”—there are a few experimental drugs available, some of which haven’t been tested on humans—“but doctors can treat its symptoms.”

Nobody is sure yet how the virus started continent hopping and infecting so many patients without any recent travel to Africa. One victim in London visited Nigeria in late April, but none of the other individuals infected in the U.K. reported contact with that person.

In Africa, the disease passes to humans via contact with animals, typically thought to be small rodents. (It’s called “monkeypox” because it was first discovered in 1958 among colonies of research monkeys, but the animal reservoir host is actually unknown.) From there, transmission between people “is thought to occur primarily through large respiratory droplets,” according to the CDC, like those expelled by coughing or sneezing. You can also contract it by touching someone’s infected lesions, or from contaminated items like clothes or bedding. But at least with the West African genetic group that has gone global, human-to-human spread is usually thought to be pretty limited. (The Congo basin version seems to be a somewhat different story.)

“It’s really someone coughing and in close proximity. It’s not something that you are going to get just walking by someone,” Dr. Daniel Bausch, president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, told the Boston Globe.

(As you may recall, scientists initially thought COVID was spread primarily through large droplets and contaminated surfaces—aka fomite—as well, before concluding it actually passed through much smaller aerosol droplets that could remain in the air much longer. I’m not—I repeat absolutely not—trying to imply a similar mistake is being made here, but in case you’re getting a slight feeling of déjà vu while reading, that’s probably why.)

This is not the first time monkeypox has made its way to the United States; dozens of Midwesterners caught the disease in 2003 thanks to—not making this up—pet prairie dogs that had been infected by animals imported from Africa. But scientists and public health experts are unsure how this latest outbreak is traveling, and are concerned that it may be spreading through communities through a new mechanism.

One theory gaining steam is that the disease may be sexually transmitted, in part because a large share of the patients who’ve been identified are gay and bisexual men. However, that might be an artifact of how health officials are tracking down cases: Many countries have been calling sexual health clinics and asking them to be on the lookout for anybody with an odd rash. As one World Health Organization official put it, “We’re finding where we’re looking.” The president of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV cautioned that, “One thing that we don’t know for certain yet is whether the reason we’re seeing it in gay men is because they’re going to clinics.”

So a physically horrific, potentially deadly illness that typically doesn’t spread far outside Africa is snaking its way through Europe, the U.K., and North America, and nobody has a clear idea why or how yet. On the bright side, scientists don’t think it’s that transmissible. and the smallpox vaccine—of which the U.S. has stockpiled enough to inoculate every single American—provides substantial protection against monkeypox. One of the reasons this disease is re-emerging is that countries stopped vaccinating people for smallpox after it was eradicated in 1980. If infections do somehow start to spiral, the government can start offering shots, and presumably a lot Americans will happily take them.

Meanwhile, public health experts are all more or less urging calm. “This is not a disease that is going to sweep across the country,” Dr. Bausch told CNN this week. In the Washington Post, Tom Inglesby, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, reassured that “the risk to the general public at this point, from the information we have, is very, very low.” Dr. Agam Rao of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens told NBC that “I would not want people to be too terribly alarmed right now and to be changing their behaviors too much”; he also noted that people who catch the West African edition of monkeypox “typically recover pretty well.”

Now, the public health community has not exactly covered itself in glory in the coronavirus era. (I think we’re all tired of “noble lies” at this point.) But as someone who still has some residual faith in expertise, the rational half of my brain still finds their general lack of alarm soothing. Also, there just haven’t been that many infections thus far, and given that it’s spread almost entirely through sustained, close contact, there really is no logical reason to set off the freakout siren.

And yet, I still kind of want to shriek like mad with every new headline about this thing. After everything that’s happened in the past two years, the world is dealing with a literal pox upon its house. How is this real? How!?